Stained by Period Blood, Girls Are Pushed Out of School

Malagen investigates how poverty, stigma and myths deny girls access to menstrual hygiene products, forcing them to miss critical school hours, fall behind in their studies or even drop out of school entirely

Story by Kaddy Jawo

“I plead with anyone who can help underprivileged girls like me in the rural areas. I want to stay in school, but when my monthly period comes, I stay at home for days on end and my grades keep going down.”

It is a cry from the heart.

Maimuna, 17, cannot help the note of envy that creeps into her voice as she talks about urban girls who she believes do not have to suffer her fate.

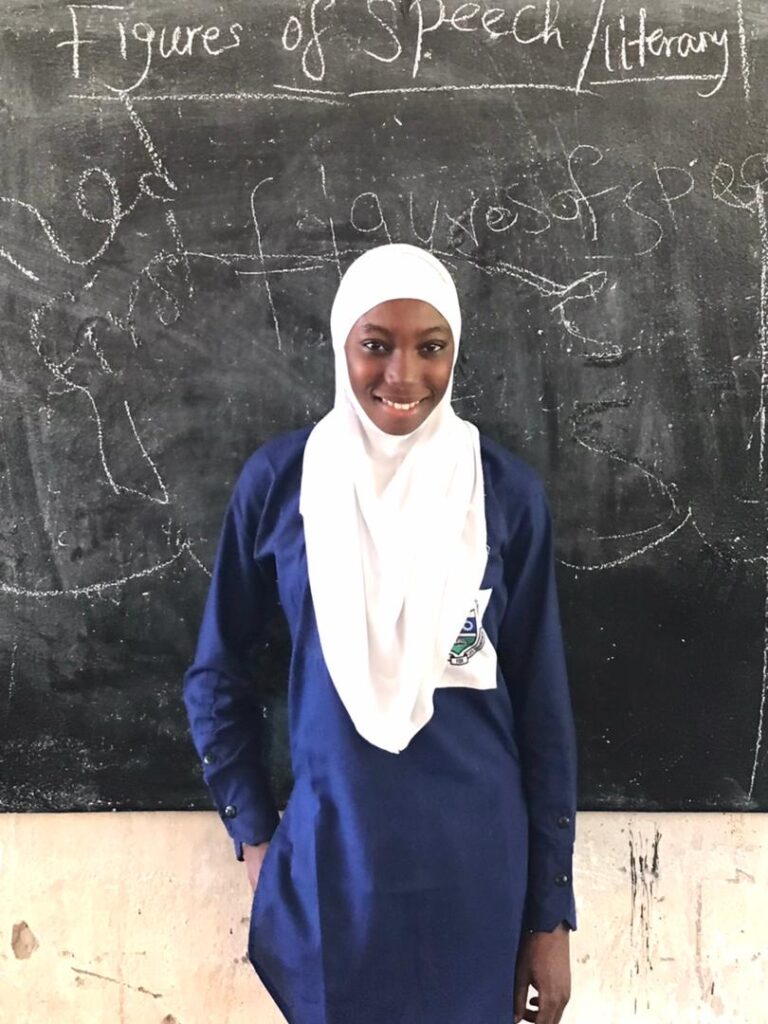

“We’re not as lucky as students in [urban Gambia], who have access to sanitary pads,” the student of Bakadagi Senior Secondary School in the rural Upper River Region (URR) told Malagen in a recent interview.

Her story is shared by Kaddijatou, 16, from Nyakoi, in Wuli, also in the URR.

From a young age, she was sure that academic success was her ticket out of the poverty she was growing up in. So, she puts all her efforts into her schoolwork. And it was paying off: she emerged as the best Grade 8 student at Nyakoi Junior Secondary School.

But since reaching adolescence, she’s been missing school hours and struggles to catch up each time she returns. Her performance has taken a hit, and she fears dropping out due to period poverty – defined as inability to afford and access menstrual products.

Stolen education

The United Nations recognises menstrual hygiene – including access to hygiene products – as a basic human right. Yet it is denied to millions of women and girls worldwide.

For many girls in Gambian schools, sanitary pads are either unavailable or an unaffordable luxury. Others do not use it due to myths and stigma. For these girls, staying home until their period is over becomes an ideal option.

The extent to which period poverty impacts school girls in the country remains unclear.

However, several school administrators told Malagen that they have seen many brilliant girls fall behind or drop out of school as a result.

“We don’t keep the records. So I can’t say for sure how many,” said Ruggy Bah, a teacher at Nyakoi.

Tida, the head girl of Bakadaji Senior Secondary School, said two of her schoolmates were married off because of constant absenteeism due to menstruation.

A 2010 survey by the Ministry of Basic and Secondary Education shows that girls miss 10 to 20 percent of school hours due to menstruation.

However, when provided with pads, the girls’ attendance and performance improved as they have ‘enhanced concentration, and higher confidence.’

Price of a pad is a girl’s education

Period poverty is widespread among students in the rural communities of Upper River and Central River of The Gambia, Malagen has gathered.

But they are not alone.

The use of rags, cotton wool and tissue paper during menstruation, instead of sanitary pads, is believed to be widespread in the country.

In the Lower River Region, three out of every ten women and girls use rags and old pieces of cloth, according to a 2020 UNFPA survey.

“Difficulty affording menstrual products can cause girls to stay home from school and work, with lasting consequences on their education and economic opportunities,” the study says.

Some of the most affordable pads found in the shops cost up to D50 (approx. 70 cents) per packet. A packet contains 10 or 12 pieces, meaning two or three packets would be needed every month – D150 (approx. $2).

In a country where every dalasi counts, and an estimated 15 percent of the population live on less than a dollar a day, the price of menstrual hygiene becomes too big a burden for many.

The girls pay the price with their education.

Pads are whiteman’s trap

As part of our social experiment, Malagen offered a few packs of sanitary pads to a group of girls in Bakadaji. They politely declined the offer.

“Our mothers will question us ,” said Jaka, one of them. “I can’t take it home.”

Like Jaka, Fatoumata was told by her mother that using pads would cause her to lose her virginity.

“My mother said pad is a whiteman’s trap,” she said, echoing a deeper suspicion about the use of Western products when it comes to intimate health.

In a society that places a premium on virginity, many girls would rather endure the discomfort of old pieces of cloth and rags than risk the shaming that comes with using pads.

Our Girls don’t know what pads look like

And beyond myth and affordability, there is unavailability.

“Some of the girls do not know what sanitary pads look like,” said school head girl, Tida of Bakadagi.

Malagen visited a local shop in the outskirts of Basse, the administrative and business capital of the Upper River Region to enquire about sanitary pads.

“I’ve been a shopkeeper for nearly a decade, but I do not know pads and I don’t sell them,” Saidou Jallow, a shopkeeper, told us.

The absence of proper sanitary facilities and access to clean water sources complicate matters for girls in these rural communities.

“Sometimes we go for weeks without water in school and when our borehole stops working, it is difficult for us,” a student at Bakadaji said.

“Even though we use latrines, the discomfort is always there when we are on our period,” another one added.

Urban girls are not spared.

While girls in the rural areas may believe that their peers in urban areas are not affected by period poverty, the reality seems different.

Maimuna Jallow, the head girl at Latrikunda Upper Basic School in Serrekunda, said although access to sanitary products may not be as limited, issues of affordability, myths and stigma are very real in spite of advocacy efforts by social clubs.

“Sometimes you find girls shaming their colleagues. Some of the teachers are also inconsiderate towards girls who are on their period,” she said.

Abdoulie Jah, the headboy of Latrikunda Upper Basic School, said he has been advocating for increased awareness and support for female students.

“We have sanitary pads available for free at the principal’s office, but the girls are often too shy to make requests,” he said.

Kura Jobe, the school’s principal, confirmed this and described it as regrettable.

The fight against period poverty

Support for girls in their silent battle against period poverty may not be entirely absent even if visibly acutely inadequate.

In a study seen by Malagen, the ministry says an estimated five million dalasis would be needed annually to provide sanitary pads to school girls.

“The ministry [of basic education] used to supply sanitary pads to schools but we have no idea why they stopped,” a teacher, Rugey Bah, queried.

Tida Jatta, a senior official at the ministry knows why: lack of funding.

Now, there’s a curriculum on menstrual hygiene to be taught in schools.

There’s an app being built, Suma Tyme, to provide young people with information on sexual and reproductive health.

There’s a study being done on the extent and impact of period poverty in schools.

There’s even a community led project, Basse Pad Production Centre, that produces reusable sanitary pads to make it more affordable.

“Our goal is to reach every young person with accurate information, whether they are in school or out of school,” said Rose Sarr, the UNFPA Country Representative, whose organisation supports those efforts.

However, rural girls like Maimuna and Kaddijatou are yet to benefit from such ‘groundbreaking transformative’ initiatives.

This story is published as part of the OMC Investigative Reporting Fellowship, jointly funded by U.S Embassy in Banjul and Freedom House-The Gambia.

Malagen investigates how poverty, stigma and myths deny girls access to menstrual hygiene products, forcing them to miss critical school hours, fall behind in their studies or even drop out of school entirely

- Explainer: Can NPP Keep Seat Against Opposition Alliance in Half-Die Vote

- Hate Speech Alert: NPP Supporter Targets PPP Candidate in Half-Die By-Election

- Michael Correa Found Guilty of Torture in Historic U.S. Verdict

- Explainer: Why Is the IEC Holding a By-Election in Banjul Half-Die Ward?

- Explainer: How the IEC Chairman Is Appointed in The Gambia