A Foreign-owned Fishmeal Factory Causes a Stink in Senegal

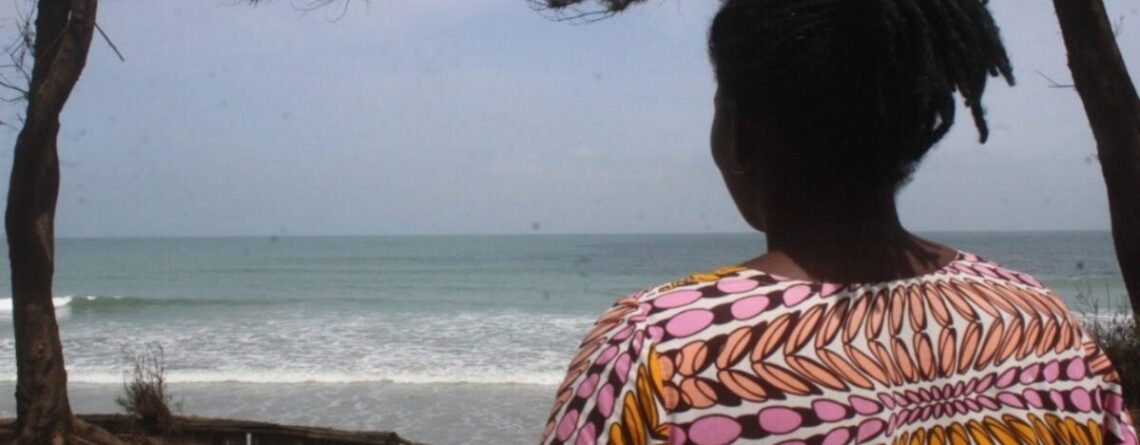

Standing beside the empty guest house she manages, Abie Sanyang looks with worry across the beach. The source of her concern is less than 100m away on the foreshore; a fishmeal factory – its silos looming over a concrete wall separating it from cheerfully decorated palm-thatched beach bars and settlements.

The fishing village Abene, in the rural Casamance region of southern Senegal, has long been a popular tourist destination. But when the plant, Société des Produits Halieutiques (SPH SARL), began operating in April 2018, the noxious fumes created in the process of turning pelagic fish into powder and oil drove visitors away.

“Our guests were struggling to breath fresh air. They cannot have a good time eating here because of the bad smell from the fishmeal plant,” says Sanyang.

During its short period of operation, the factory also caused pollution in the marine protected area in which Abene lies, has contributed to food insecurity and created divisions within the community of around 4,000 inhabitants.

Operations were temporarily suspended in July 2018 following protests by youths and environmental activists that led to a community referendum. The plant has remained shuttered to date. But concerns are growing that fishmeal production will soon resume amid claims of a recent change of ownership.

The situation in Abene mirrors fishmeal and fish oil development and investment in the wider region, where more than 50 mostly foreign-owned plants have been built along the coast of Senegal, The Gambia, and Mauritania, targeting small pelagics, oily fish such as sardinella and bonga that congregate in vast shoals off West Africa. Latest figures show that West Africa’s trade in fish meal and fish oil has grown tenfold between 2010 and 2019 – from about 13,000 tonnes to over 170,000 tonnes.

In the last 10 years, eight fishmeal plants have been established in Senegal. Currently only six are functional.

Much of this fish is caught in huge volumes by industrial trawlers, and the lack of data on the catches makes it difficult to implement conservation measures or catch limits. “The massive presence of investors coming to set up fishmeal and fish oil plants in West Africa may be due to inadequate public fisheries policies that prioritise the sustainable management of fisheries resources,” says Abdoulaye Ndiaye, ocean campaigner for Greenpeace Africa, based in Senegal’s capital Dakar.

The factories have made it more lucrative for local fishermen to sell their catch to them, rather than at local markets, diverting a vital source of animal protein for the local populations.

More than half a million tonnes of fish used to produce fishmeal and fish oil exported from West Africa to Europe and Asia for use in aquaculture and animal feed could feed some 33 million people instead, a recent Greenpeace report found.

Many of the contracts awarded to the operators are opaque, Ndiaye adds. “The lack of transparency in the public management of the authorisation given to these fishmeal factories is also one of the causes of the proliferation of these factories in West Africa.”

A broken promise

The Abene plant has been mired in controversy from the start and many in the community now believe they were duped into agreeing to its development.

A business directory search of fishmeal factories in Senegal did not reveal the ownership of the SPH plant at the time it was operating. However, sources in the community told China Dialogue that the promotors who met with community leaders were Chinese.

The promotors promised the new plant would bring investment into community infrastructure, including a new road and hospital and much-needed local jobs. Women and youths were not invited to these meetings.

“They [the owners] bypassed all the legal processes of bringing up investment. They selected a few people including the elders and worked with them. No doubt those people were corrupted,” argues Kutubo Sonko, former President of the Abene Youth Association. “Imagine flying a few to Dakar, those who never had a bike, and flying them to Dakar means a lot to them. They agreed with everything said [by the investors] in Dakar.”

In December 2017, investors were granted a building permit from Senegal’s Fisheries and Maritime Economy Ministry for an ice plant, intended to support the local fishing industry.

Later that month, the ministry approved changes for the plant to move to the production of fishmeal and fish oil. A report at the time claimed that the “ice plant” was simply a disguise of the fishmeal plant from the beginning, and the locals did not know about the fishmeal plant until it started operating in 2018.

The plant has never been the subject of an Environmental and Social Impacts Assessment (ESIA) which is a legal requirement for every national fishmeal plant, according to Kutubo Sonko. In addition, the Environmental Code stipulates that such industrial complexes cannot be located less than 500 meters from homes. But when China Dialogue visited Abene in May, it was evident that the plant was in much closer proximity to residential homes and hospitality sites than the regulations allow.

Almost immediately after it began operations, polluting discharge was witnessed, with reports of unbearable smells, black smoke and untreated waste.

“I saw the discharge of the waste of toxic water in our rice farms,” says Kebba Sonko, the current president of the Abene Youths Association. “ … all those nearby garden wells were contaminated and the cattle owners were even driving their cattle away from the area.”

The beach also became littered with dead fish that had washed ashore. The same phenomenon was already being seen just a few kilometres up the coast in neighbouring Gambia in areas where fishmeal factories are based.

Lieutenant Abdoulie Sanyang, the Marine Protection Area Commander for Abene, says that samples were taken of the dead fish on Abene’s beach but these proved inconclusive. “The problem is that Abene is close to Kartong [in the Gambia] and we can’t determine if the water contamination [has been] done by the fishmeal plant in Kartong or Abene,” he explains.

In May 2018, a local campaign was launched with several online petitions. Called “SOS to save the Yaboye’ (yayobe means sardinella in Wolof), it aimed to raise awareness with open-air screenings of a documentary, Poisson d’or, poisson africaine, which examines the impact of the fishmeal factory on the traditional fishing practices of the region.

In June 2018, the Minister of the Environment, Mame Thierno Dienga, instructed Governor Guedj Diouf to hold a referendum on the fishmeal plant to decide whether the community wanted the fishmeal plant or not. The results showed that 93% of the 500-600 respondents were against the plant’s operation. Six villages – Abene, Djannah, Kabadio, Niafrang, Colomba, Bambadjiaky – also submitted a memorandum citing their refusal to live next to a “killer” and “toxic” industry.

Youths, who were initially in favour of the development of the factory, turned against it as it became clear that their hopes that it would bring new job opportunities were not going to materialise. In fact, the factory did not employ anyone from the local community, and only a handful of youths during its construction.

Rather than improving the flow of money into the community, the factory has had the opposite effect.

Abene’s once thriving tourism sector, which attracted tens of thousands of visitors a year to its annual music festival and rich cultural scene has been in limbo since 2018. Many tourist lodges and restaurants were forced out of business when visitors stopped coming and investment into reopening is on hold while the future of the factory remains uncertain. Locals say reopening of the factory would be the final nail in the coffin for what is left of Abene’s tourism sector.

“If the factory resumes operations I will lose my job,” says Abie Sanyang.

Up and down the coastline of Senegal and the Gambia, the decision to allow fishmeal production into communities has proved divisive, threatening the livelihoods of artisanal fishers and the food security of communities that depend on pelagic fish as a cheap source of protein.